per chi non capisse l'inglese o non ha voglia di tradurselo sotto trovate l'articolo scarno nella versione web in italiano su repubblica del 15\4\2017

Leipzig flat made famous in Capa war photo becomes poignant memorial

Apartment featured in one of the most memorable images of the second world war restored to its former glory

American soldiers in the Leipzig apartment building now known as the Capa House. Photograph: Robert Capa © International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos

American soldiers in the Leipzig apartment building now known as the Capa House. Photograph: Robert Capa © International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos

Thursday 1 September 2016 13.00 BSTLast modified on Friday 11 November 2016 11.35 GMT

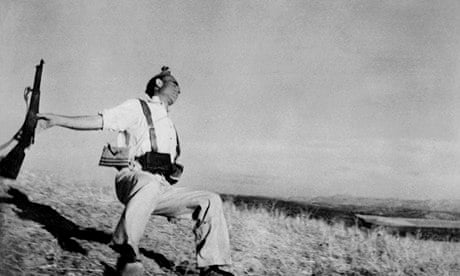

Robert Capa called them his most definitive images of the second world war. Seconds after the photographer had taken a portrait of a fresh-faced sergeant poised with a heavy machine gun on a Leipzig balcony, the soldier slumped to the floor. On 18 April 1945, in the final days of the conflict, he had been hit and killed by the bullets of a German sniper.

Capa climbed through a balcony window into the flat to photograph the dead man, who lay in the open door, a looted Luftwaffe sheepskin helmet on his head. The subsequent series of photographs show the rapid spread of the soldier’s blood across the parquet floor as other GIs attended to him and his fellow gunner took over his post at the machine gun.

“It was a very clean, somehow very beautiful death and I think that’s what I remember most from the war,” Capa recalled two years later in a radio interview.

The images were wired back to New York and featured prominently in Life magazine’s Victory edition on 14 May. The soldier, Raymond J Bowman, 21, of Rochester, New York, was later hailed as The Last Man to Die by Capa and the photographs would become some of the most memorable images of the second world war.

But their origins would have remained obscure had a group of Leipzigers interested in highlighting and preserving the city’s little-known Capa connection not discovered that a derelict 19th-century apartment block was where the photographer, embedded with the US army during the capture of the city, had taken the pictures.

Learning that the building was destined for demolition four years ago, the group set about trying to save it. And save it they have: following a €10.5m (£9m) refurbishment, including shoring up the foundations and replacing the balconies, the Capa Haus has been restored to its former glory.

The Leipzig apartment building after a fire on New Year’s Eve 2011 when it was scheduled for demolition. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

The Capa House after restoration in 2016. Photograph: Alamy Stock Photo

Strips of Jahnallee have been renamed Bowman Strasse and Capa Strasse. In the elegant ground floor Cafe Eigler a permanent exhibition is dedicated to The Last Man series and other Capa pictures which tell the story of 18 April.

“There was very little in the city to recall the last days of [the second world war],” said Meigl Hoffmann, “and we were struck by what a poignant and authentic memorial this actually was.”

Hoffman, 48, a Leipzig political cabaret artist and one of the founding members of the Capa Haus initiative, grew up with the many wartime stories of his parents and grandparents. But the US army’s role in liberating Leipzig from nazism had been an unfashionable version of events during the days of communism when the dominant story was of how the Red Army – which arrived in July – had saved his city.

“As a result the Capa connection had been suppressed because his pictures told the unfavourable story of the US troops, and so for years no one here really knew about them, they were considered subversive,” said Hoffmann.

Capa’s picture of the American soldier killed by a German sniper on 18 April 1945. Photograph: Robert Capa © International Center of Photography / Magnum Photos

He discovered the Last Man to Die images in a banned underground magazine at the age of 19. “I was electrified by the pictures – they appeared 3D to me, and because a lot of the photos we knew in the East German era were in black and white, they struck me as being very contemporary,” Hoffmann explained.

He and a friend set about trying to locate the balcony, aided by Capa’s description of the “big apartment building that overlooked the bridge” on which German soldiers “were putting up considerable resistance”, as well as visual references in the photograph itself. “But the only building that matched the description didn’t seem to fit at all, as it had no balcony,” said Hoffmann.

The place he found – Jahnallee 61 – was on a busy crossroads in the west of the city. He clambered with trepidation through its broken ceilings and floorboards, finding the “nice bourgeois apartment” on the second floor as Capa had described it, a shell of its former self. The renamed Capa Strasse.

The renamed Capa Strasse.

The renamed Capa Strasse.

The renamed Capa Strasse.

But, surprisingly, unlike the rest of the building, it was largely intact – apart from the fact that its balcony, close to collapse, had been removed years before – and it still had the commanding, unobstructed view of the Zeppelin Bridge.

With weeks to go before the wrecking ball was due to knock it down, the initiative contacted US war veterans involved in the battle for Leipzig.Bowman, the fifth of seven children, had been sent to Europe with Company D of the 23rd Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Infantry Division. He was taking it in turns with his fellow gunner, Lehman Riggs, 24, to operate the .30 calibre Browning.

Riggs had just stepped back inside the apartment and was reloading the gun as the fatal bullet struck. The grandfather clock behind which Riggs took shelter showed – in brighter exposures of the photographs – that Bowman died at 3.15pm.

Riggs, now 96 and living in Cookeville, Tennessee, said his memories of the incident had rushed back during a recent return visit to the apartment.

|

| Robert Capa was embedded with US troops. Photograph: Time Life Pictures/Getty Image |

“The event had so disturbed my mind because of the loss of my buddy, I had tried to block it, and hadn’t talked about it for years,” the retired postal worker said. “But returning to the scene unlocked all the memories.”

He recalled Bowman as a “very kind young man”. “I was 3ft from him when it happened. I could have reached out and touched him, but I knew he was dead. I had to carry on in his place, as I’d been trained to do.”

Events had happened so fast, he said, from the order to “run into an upper floor of the house and offer cover for our troops so they could come across the bridge”, to the death of his partner, that he had been unaware of Capa’s presence.Read more “In combat we often had army photographers with us. I thought he was just another one of those.”

He contacted his wife to buy Life magazine on learning that he featured in it, but described it as “extremely painful” to view the pictures once he returned from the war, “as they made me vividly relive what had happened”.

Robert Capa: 'The best picture I ever took' - transcript

Read more “In combat we often had army photographers with us. I thought he was just another one of those.”

He contacted his wife to buy Life magazine on learning that he featured in it, but described it as “extremely painful” to view the pictures once he returned from the war, “as they made me vividly relive what had happened”.

Robert Petzold, from Leipzig, who was 13 at the time, recalled the phone call he received from his grandmother the previous evening. “She lived a few kilometres further west and had seen that the Americans were arriving in Leipzig,” he said.

“She told us: ‘The enemy is coming, have a hearty breakfast.’”After doing just that, he, his mother and sister took cover in the air raid shelter in the basement and, while they could hear the heavy exchange of fire, they had little inkling of the drama that had unfolded on the balcony where, Petzold recalled, “I used to keep rabbits.”

Once they were given the all-clear, his mother returned to their flat to the horrifying scene of the dead soldier in her living room. “His blood was all over the floor, and soaked into a rug. On a dresser in the hallway she found letters and photographs that had been removed from his pocket, showing a woman and children. She said: ‘They may be our enemies, but they suffer the same fate as us,’” Petzold said.

For years, he said, his mother tried in vain to remove the blood stains from the rug. “But nothing, no chemical process, could get rid of them – they served to us as a permanent reminder of the horror of what had happened.”

The apartment’s current owner, Katrin Stein, said she tried not to think too much about what had happened there. Photograph: Kate Connolly for the Guardian

A dining room table in an adjoining room that was used by other members of the machine gun platoon had dents on its underside from the recoil motion of the gun. “The soldiers had been thoughtful enough to turn the table top upside down to avoid damaging it. My mother was always very impressed by that,” he recalled.

Raymond Bowman’s mother, Florence, at first refused to believe reports her son had died. When her other son contacted Bowman’s army unit for further confirmation, he was told to buy a copy of Life. There the family recognised the pin with the initials RB, which Bowman had made in high school.

The Capa Haus initiative, which was accompanied by personal appeals to city authorities by Riggs, Petzold and members of the Bowman family to save the historic site, led to approaches by a Munich investor, who prides himself on his track record of saving historic buildings that “tell stories”.

“It was an important picture but one that Capa almost didn’t take,” said Christoph Kaufmann, of Leipzig’s Civic History Museum and the main curator of the exhibition, pointing to Capa’s own take on the incident, in the only known recording of the photographer’s strong Hungarian-accented voice.

Lovers and fighters: Robert Capa's best second world war photography

“He’d just moved on to the open balcony and put up that heavy machine gun,” Capa said. “But God, the war was over, who wanted to see one more picture of somebody shooting? … But he looked so clean-cut and he was one of the men who looked like if it would be the first day of the war he still was earnest about it … So I said: ‘All right, this will be my last picture of war.’ And I put my camera and took a portrait shot of him.”

Katrin Stein now lives in the apartment, her balcony painted peach-pink and adorned with geraniums and a wash stand.

“I try not to think too much about what happened here,” she said, standing in the balcony doorway where Bowman fell. “But it certainly adds another dimension to the history I learned in school.”

da repubblica del 16\4\2017

DALLA NOSTRA CORRISPONDENTE

BERLINO.

Aprile 1945. Sono gli ultimi giorni del Reich, gli americani stanno conquistando Lipsia. Un soldato individua una casa in una posizione strategica, si affaccia dal balcone e punta il mitra verso la città vecchia, dove i nazisti stanno battendo in ritirata. Il proiettile di un cecchino tedesco, nascosto chissà dove, lo centra in mezzo agli occhi. Raymond J. Bowman cade riverso, l'elmetto si storce nell'impatto con la finestra, il sangue riempie il pavimento. Dietro di lui, c'è uno dei più grandi fotografi di guerra del Novecento, Robert Capa, arrivato in Germania con le truppe americane. Il 18 aprile la sua foto del soldato morto viene pubblicata sulla rivista Life.

Passerà alla storia con la didascalia del suo autore: "last man to die", "l'ultimo uomo a morire".

Negli anni del dopoguerra, nella Germania comunista la memoria collettiva cancella Capa e gli americani. Ma il piccolo Meigl Hoffman, un quarto di secolo dopo, trova in soffitta proiettili e un elmetto "yankee", sente sussurrare in famiglia le imprese dei liberatori americani, censurati dai libri di storia del socialismo reale. Alla fine degli anni '80, arriva il momento che gli cambierà la vita. Su una rivista clandestina, Snowbag Magazine, trova cinque foto di Robert Capa di quei fatidici giorni di Lipsia. Sono immagini fotografate di nascosto dall'archivio della biblioteca comunale. Meigl ne rimane stregato.

Poco dopo la caduta del Muro, il cabarettista comincia la sua ricerca della foto perduta. Contatta il consolato americano - adesso può farlo - ma nessuno ne sa niente. Anche nel 2005, durante i festeggiamenti per il 60° anniversario della fine della guerra, chiede informazioni ad alcuni veterani americani venuti in città. Ma nessuno sa fornirgli dettagli di quell'"ultimo morto" della guerra dei nazisti.

Hoffmann, allora, comincia a studiare la foto. L'unico indizio utile è il balcone in stile Jugendstil. Dopo molte ricerche riesce a individuare la strada, persino la casa. Ma la facciata è piatta. E le condizioni dell'edificio disperate. Mezzo tetto crollato, porte e finestre distrutte, calcinacci. «Il fatto è che l'edificio non aveva balconi, ed era in uno stato catastrofico », ha raccontato alla Faz. Ma lui non si scoraggia. L'intuito gli dice di insistere. Con un amico riesce a entrare nella casa, sale lentamente le scale di legno marce. In un appartamento scorge dalla finestra il deposito del tram, il benzinaio, la Zeppelin brücke. È quello che ha visto Capa, è l'appartamento dell'"ultimo soldato". È la foto ritrovata.

Ma l'impresa più difficile deve ancora venire: salvare quella casa. Hoffmann fonda un'associazione e dopo peripezie varie trova un investitore, Horst Langner, disposto a spendere 10 milioni per risanare l'edificio, giusto in tempo per salvarlo dalla demolizione, decisa dal Comune nel 2012. Oggi si chiama "Capa- Haus", ricorda il grande fotografo famoso per aver detto che «se una foto non è buona, non eri abbastanza vicino». Nel bar al pianoterra, una sala è dedicata alla storia della foto. E tra i vari testimoni dell'epoca, Hoffmann ha ritrovato anche un uomo che viveva lì da bambino, Robert Petzold. All'epoca aveva dodici anni. Sua madre vide il corpo del soldato, trovò delle foto della sua famiglia, alcune lettere. Disse ai figli: «Vedete, sarà anche il nemico, ma è un essere umano come noi».

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento